Deep Cognitive Models

Build software in the language you use to think about the business it implements

DCM aims to model the financial world in the way the human mind understands it.

Working in DCM means building a world model—a financial world model—that is online, executable, and capable of directly driving the business. It is not an offline simulation; it automates real operations—anything grounded in the notion of a contract, from order processing and trade settlement to corporate actions and all the steps in between.

Almost everything a financial institution does in digital form can be expressed directly in DCM at the conceptual level, which is essentially a business-level description. As a result, there is nothing left to code in a programming language, whether manually or via LLMs, nor any need to tailor large legacy packaged applications.

Technical artefacts—such as programming language code, services, messages, databases, and schemas—become products of inference that are materialized only when needed. They are automated out of the process of building and evolving the IT systems that run the business.

Unlike “AI” code generators, the output of DCM is not programming-language code but world models expressed in cognitive logic. Almost all processing happens at this conceptual level, without degrading into the technical level, where too much valuable information is lost in translation. Yet these conceptual models run like regular software and can interface with the lower technical level when required.

Unlike ANN/LLMs, these models are deterministic, reliable, predictable, and directly interpretable by humans because they follow the same common-sense logic as human cognition—albeit in a formal form that can run on a computer.

Unlike traditional symbolic “reasoning” systems rooted in computation, DCM is cognitive in nature: it is grounded in guiding the actions of an agent embedded in space and time, not in detached abstract symbol manipulation for theorem proving.

Traditional approach

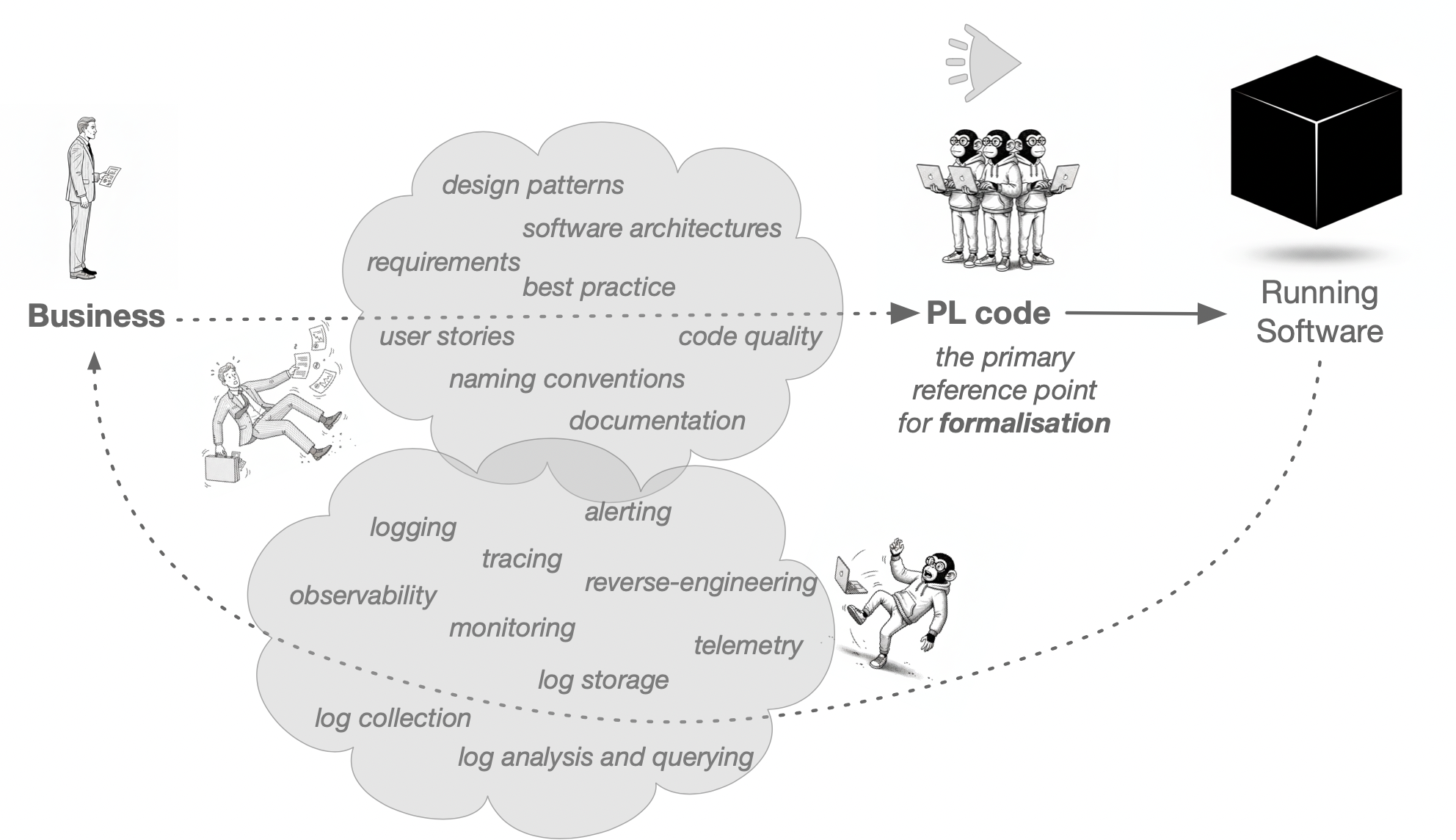

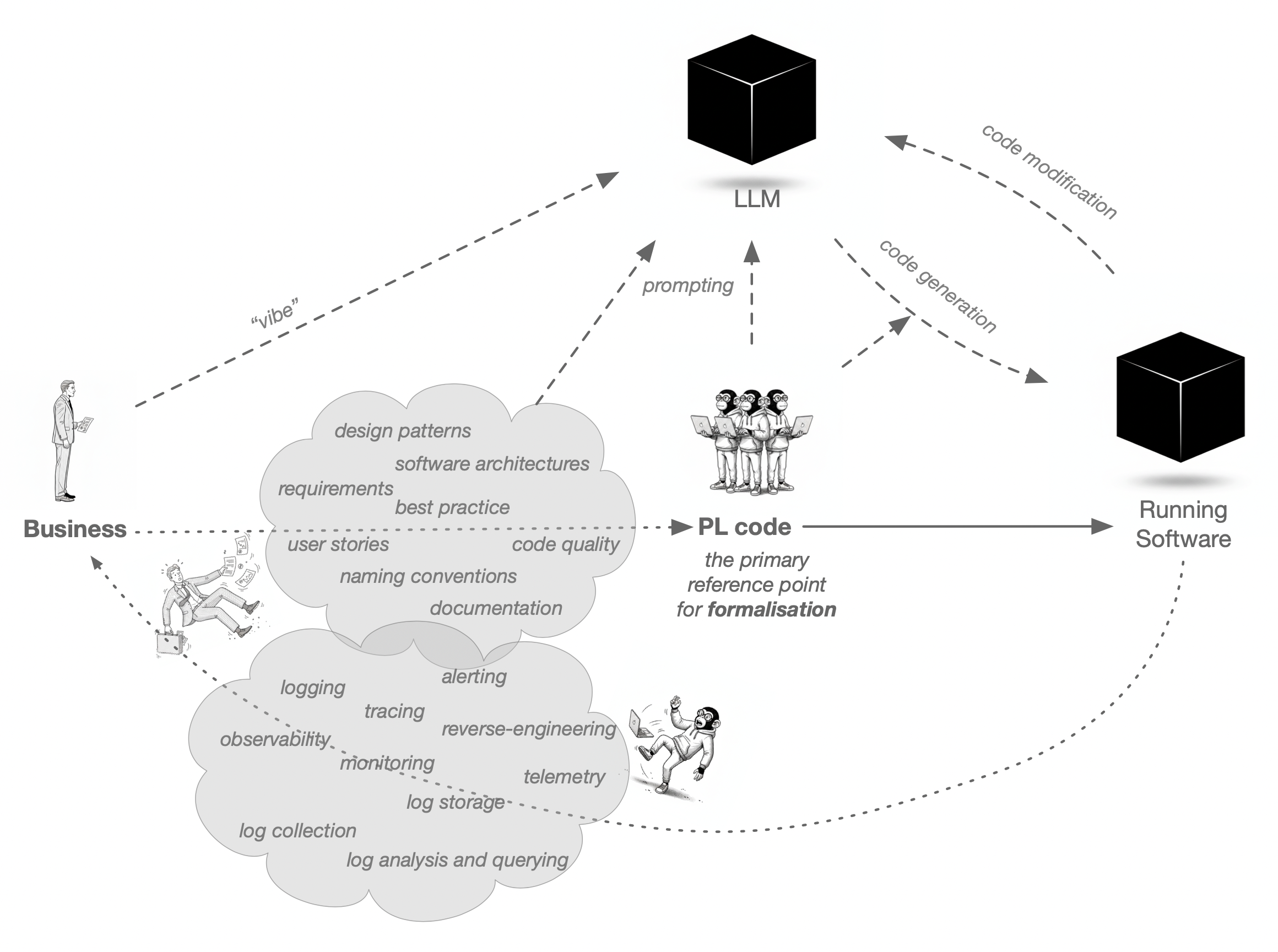

The traditional approach to developing business applications treats the low-level technical domain of programming languages as the only way to formalize a business. This makes PL code the fixed reference point for all other activities, pushing the business domain to the opposite pole of accessibility—no longer directly expressible or approachable. As a result, one is forced to embark on a lengthy and informal journey from the business side to the technical side, often losing sight of the former in service of the latter.

The business domain remains an intangible concept, loosely translated into “software requirements,” where both the process and the requirements are informal and ambiguous. We argue that this very vagueness is the root cause of many problems in software development.

At the same time, attention shifts to the technical side simply because it is easy to grasp: it is already formalized within the IT domain—programming languages, databases, messaging systems, and so on. Beginning software construction by writing message schemas, APIs, and database tables means starting at the wrong end—starting by directly encoding the technical effects.

It is the technical floor that is in the driver’s seat: that is the level of reality within which the business actually operates. There is no formal business-level counterpart to it.

All executable artefacts exist only on the technical floor; the business floor has no direct access to it and only exerts an informal, indirect influence via “requirements” submitted to the technical floor. The actual correspondence between the two floors does not exist in any formalized form—it exists only in people’s heads and is therefore not enforceable.

Traditional problems of software development do not arise from failing to follow a particular methodology—whether best practices, architectural conventions, or design patterns. These methods are merely tools for navigating an unfavorable position.

They already presuppose starting from the wrong place—the technical pole. Over time, these problems compound, until more effort is spent untangling artificially created technical issues than actually working on the business logic itself.

DCM approach

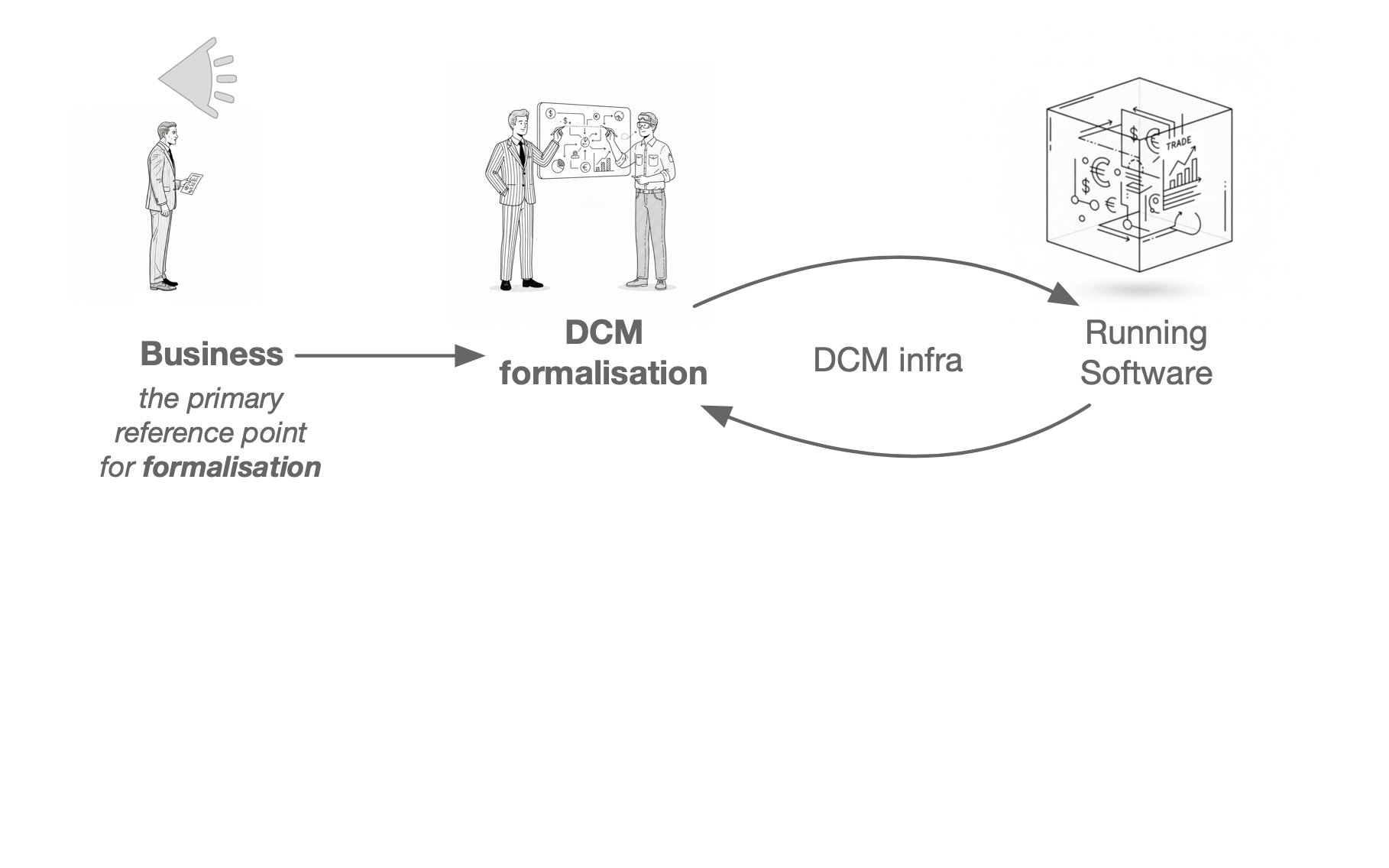

DCM starts from the opposite pole—from the business goals, not the technical means—seeking to correct this upside-down model and put it back on its feet.

DCM tackles the problem at its root: it formalizes the business domain itself and makes it directly executable—turning business logic into running software, much like geometry transforms the equation of a circle into pixels on a screen, rather than manually drawing each pixel and relying on “best practices” to approximate a round shape.

With DCM, your business logic is the code. No vague “requirements.” No costly mistranslations. Just a directly executable model of your domain, built for transparency, speed, and adaptability.

Programming languages and the frameworks built on top of them were never scientifically engineered to handle the complexities of human business domains—such as executing financial contracts. DCM, by contrast, is built from the ground up to meet this challenge, drawing on deep research in the sciences that study such domains, including cognitive and brain sciences, linguistics, perception, complex systems theory, and more.

DCM starts with goals and causes formulated independently of the technical level and can therefore leverage inferential machinery (i.e., common-sense logic) to derive technical effects automatically. Technical artefacts—such as event storage in databases or communication orchestrated via messaging systems—are generated automatically as effects of causes that are formalized at the business level.

Thus, it is the business floor that actually drives the IT system; that is the level of reality where the system is built. The technical floor is subordinate to the business floor by design—the actual construction happens mostly at the business level (at a conceptual level that corresponds very closely to the business itself).

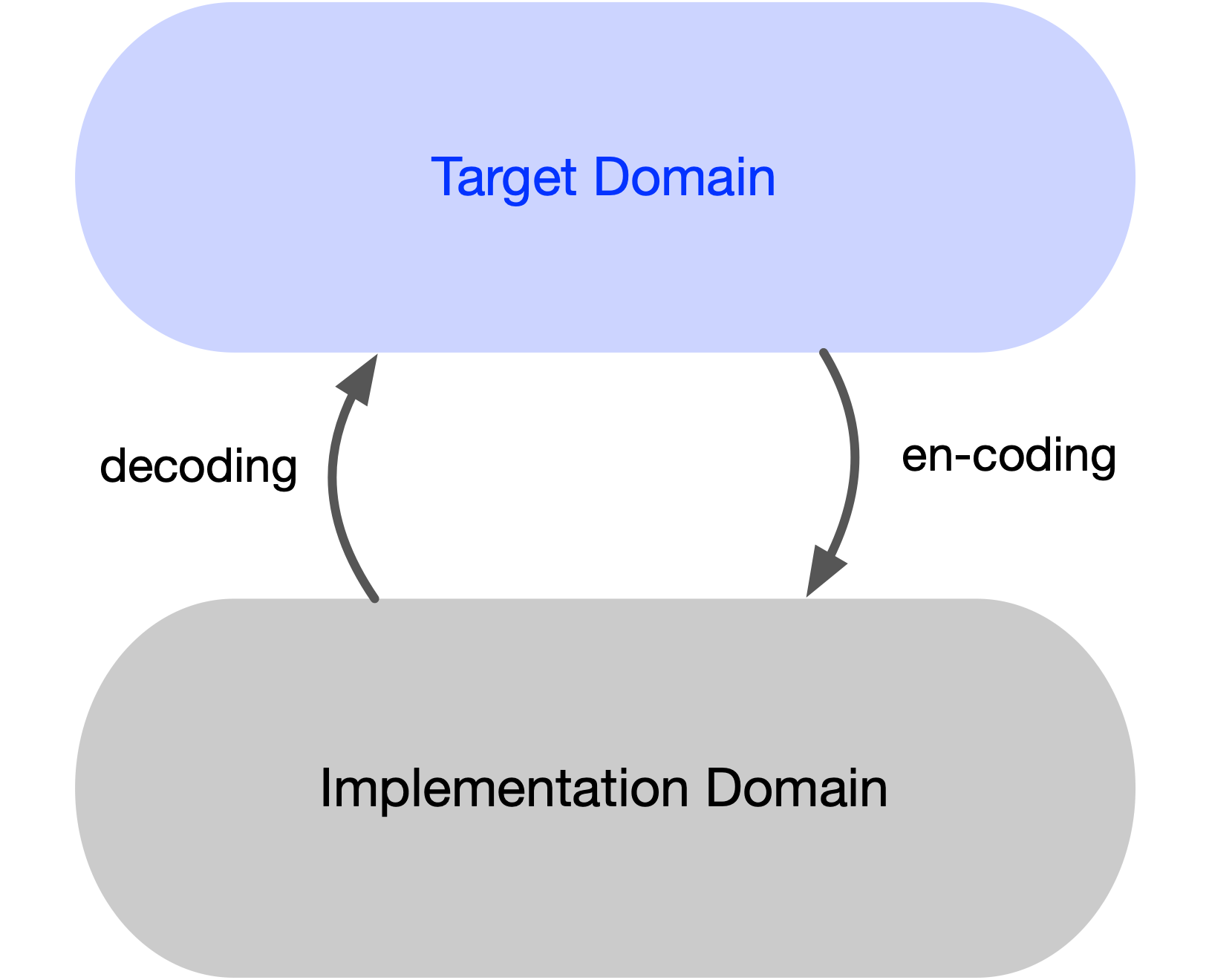

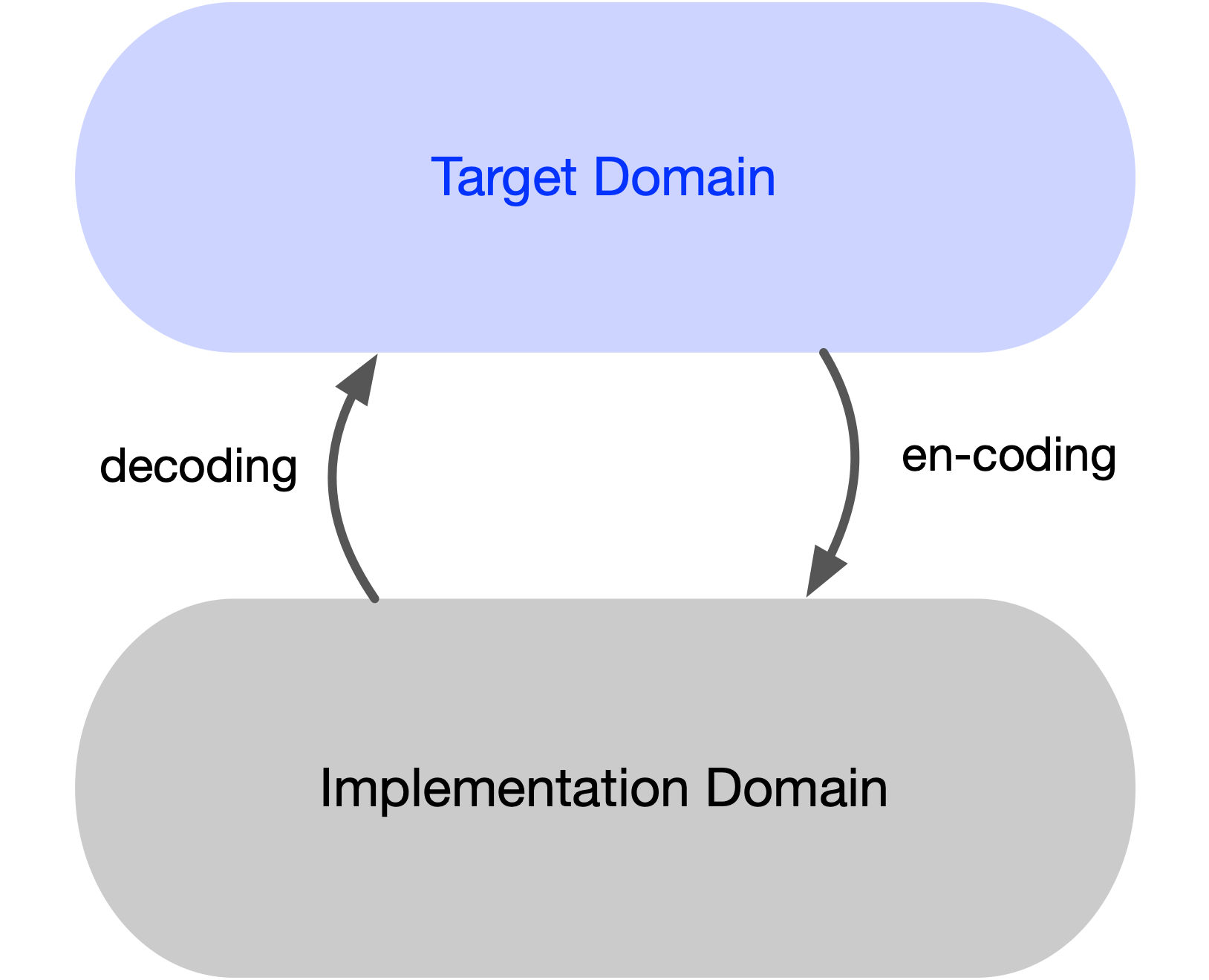

The correspondence between the two floors can be enforced and traced both upward (decoding) and downward (encoding) automatically.

AI/LLM based approach

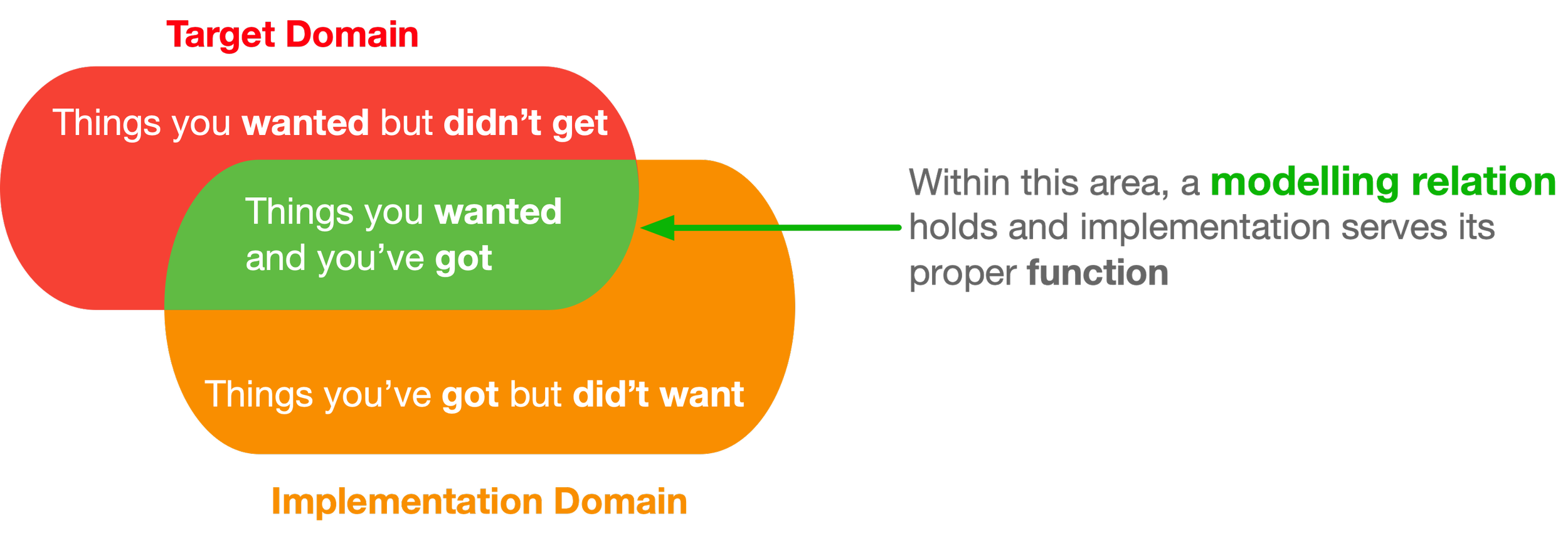

Using general-purpose LLMs directly introduces two kinds of problems: “things you wanted but did not get” and, especially, “things you got but did not want.” Both are artificial issues introduced by the tool itself, turning an initial target-domain problem into a much larger and more complex one. Taking DCM as the starting point minimizes these negative effects while still allowing ANNs to be applied on top of it where appropriate.

The amount of computational power and cost required to implement, for example, trade settlement via LLMs would be many orders of magnitude higher than doing so with DCM—even if that computation is hidden on the provider side and appears inexpensive at first.

Although LLMs may initially create the impression of a silver bullet—promising to “build software for free” with no engineering effort (prompt engineering is not engineering in the strict sense, but rather a situational skill that offers no full control over the results)—the lack of control and reliability, combined with the incommensurable complexity of the overall solution hidden under the hood, amplifies unconstrained risks in the long run. The result may be damage caused by unpredictable or unwanted behavior, as well as disproportionate effort required to diagnose and correct such behavior.

A target domain whose underlying logic is fully deterministic effectively becomes probabilistic when implemented through LLMs; one can never be entirely certain how such a system will behave in future, especially after it has undergone numerous changes.

The way modifications and changes are handled in LLM-generated software introduces another source of problems that may not be visible initially: the accumulation of errors or side effects, increasing the risk of erroneous behavior as the system grows in size and operating time.

Furthermore, LLMs operate by generating code, which reflects a problematic early move into the implementation domain. This forces one to address the target domain from within the programming-language layer—whether through a human engineer or an LLM agent—thereby reintroducing the very problems that arise when programming directly in a PL.

By contrast, DCM takes an approach in which no programming-language code is generated. Instead, the products of inference remain at the level of the target domain itself. This is possible because the core system operates at the level of structured world models rather than predicting sequences of structureless tokens.

In principle, it would be possible to train an ANN to operate over something like DCM at the foundational level, but that would be fundamentally different from current general-purpose LLMs such as Claude and similar systems.

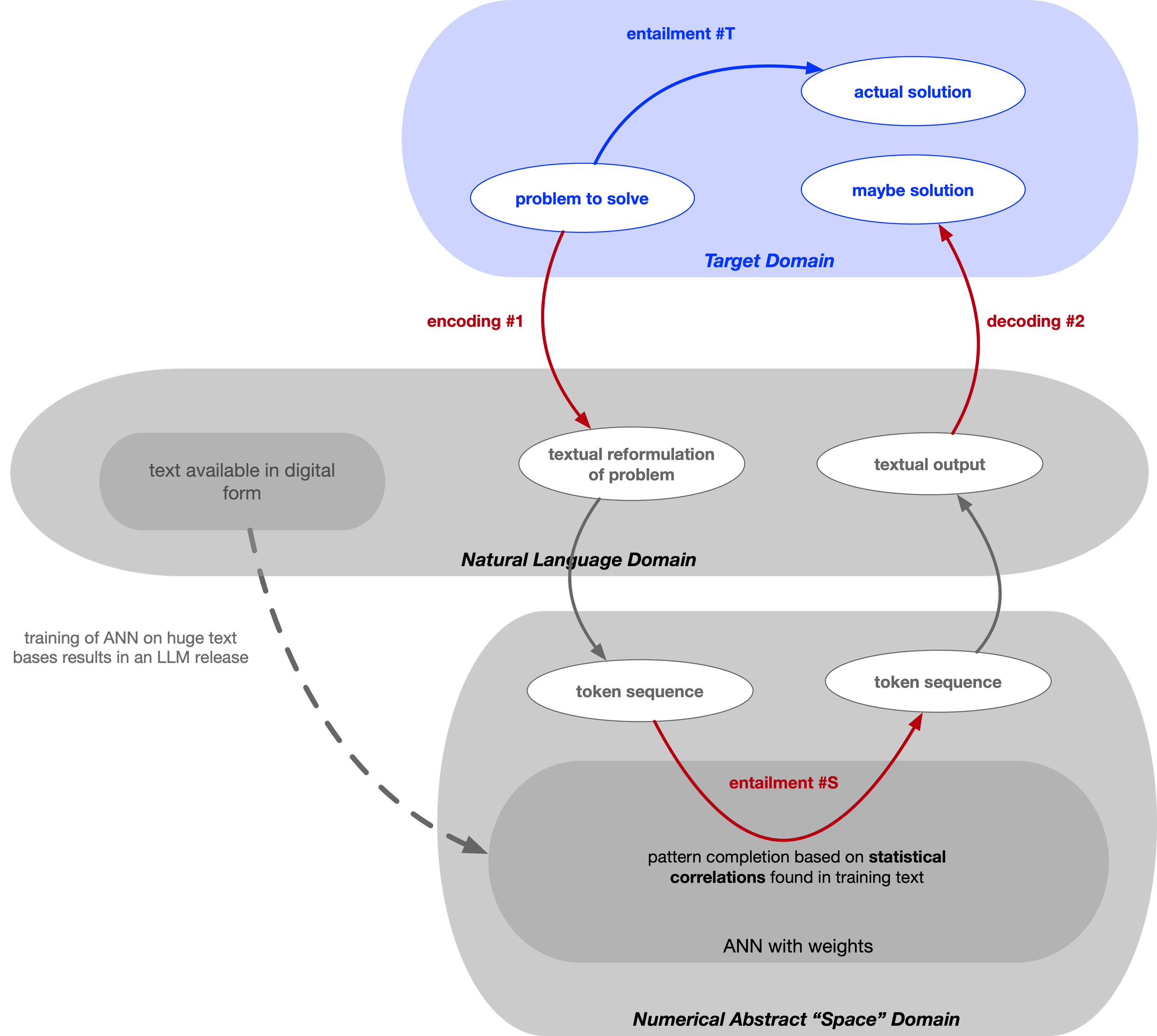

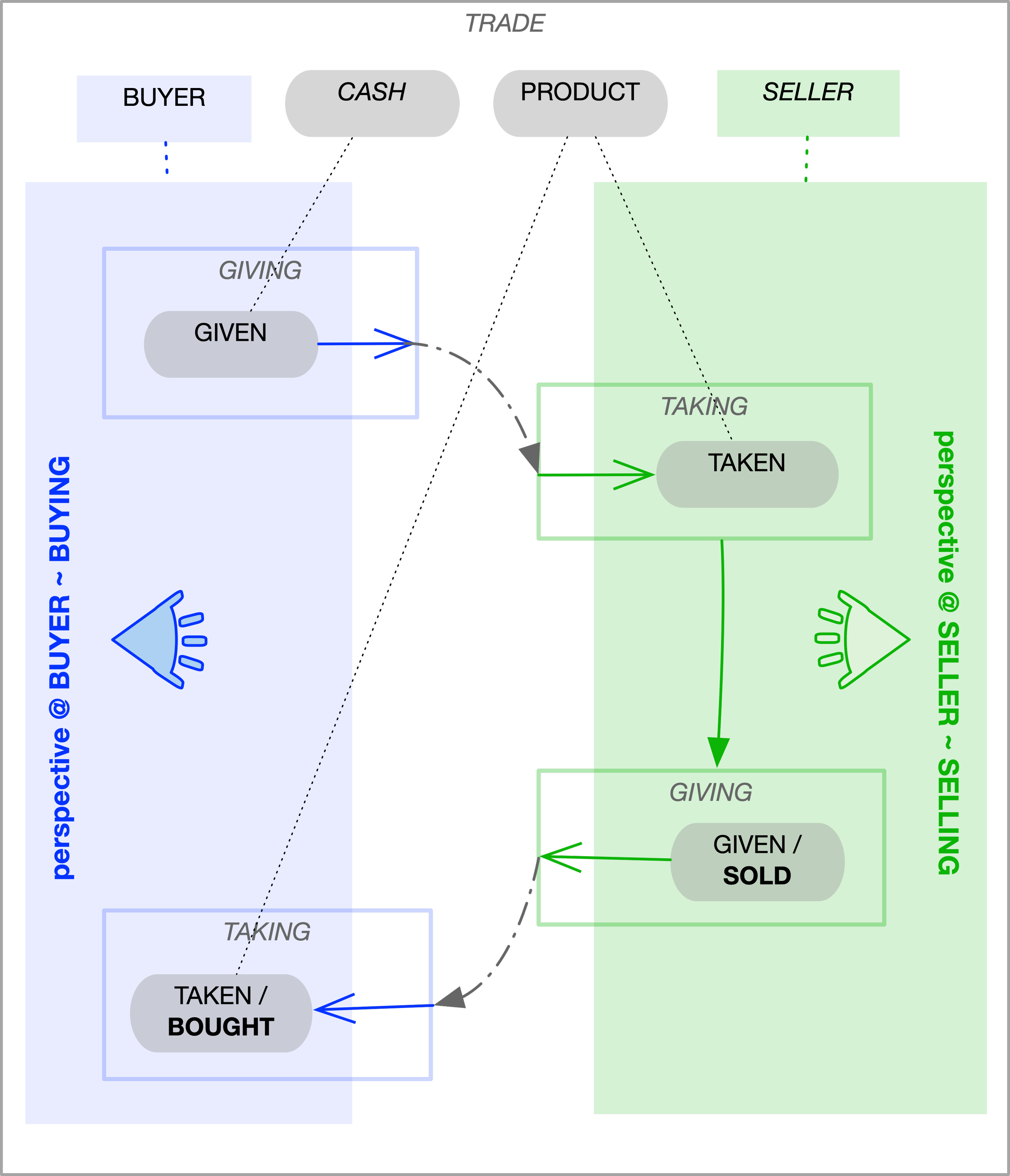

The simplified diagram illustrates where the problem arises when applying LLMs to a target domain that differs significantly from natural language—such as contract management.

The first issue is that LLMs require an additional encoding of the target-domain problem into natural language, followed later by a decoding of the solution back into the target domain. This step can lead to information loss and the introduction of noise during both encoding and decoding. In particular, when the target domain is a formal system without ambiguity, such one-to-many encodings introduce ambiguity that will accumulate and eventually backfire.

An even more serious problem is the lack of correspondence between entailments in the target domain (#T-entailments) and entailments within the LLM domain (#S-entailments). Hallucinations are an example of latent (invisible to the user) entailments within the LLM that can leak into the target domain in unpredictable ways.

Furthermore, there is no reliable way to determine in advance whether such correspondence holds, nor is there a predictable method for establishing it. In addition, an LLM cannot reliably acquire fundamentally new structural patterns after training.

Both of these problems—the encoding/decoding issue and the correspondence issue—are introduced artificially by the use of general-purpose LLMs instead of domain-specific models such as DCM.

These problems can themselves be addressed by introducing even more complexity into the overall system (such as so-called multi-agent AI architectures), but such solutions come with their own costs and risks. As is often the case, preventing errors in one part of a system merely shifts the risk elsewhere rather than eliminating it altogether.

What job is it good for?

Contract Execution and Management

Examples of trade processing concepts that are directly expressible using existing constructs in DCM—almost entirely capturing their semantics—include:

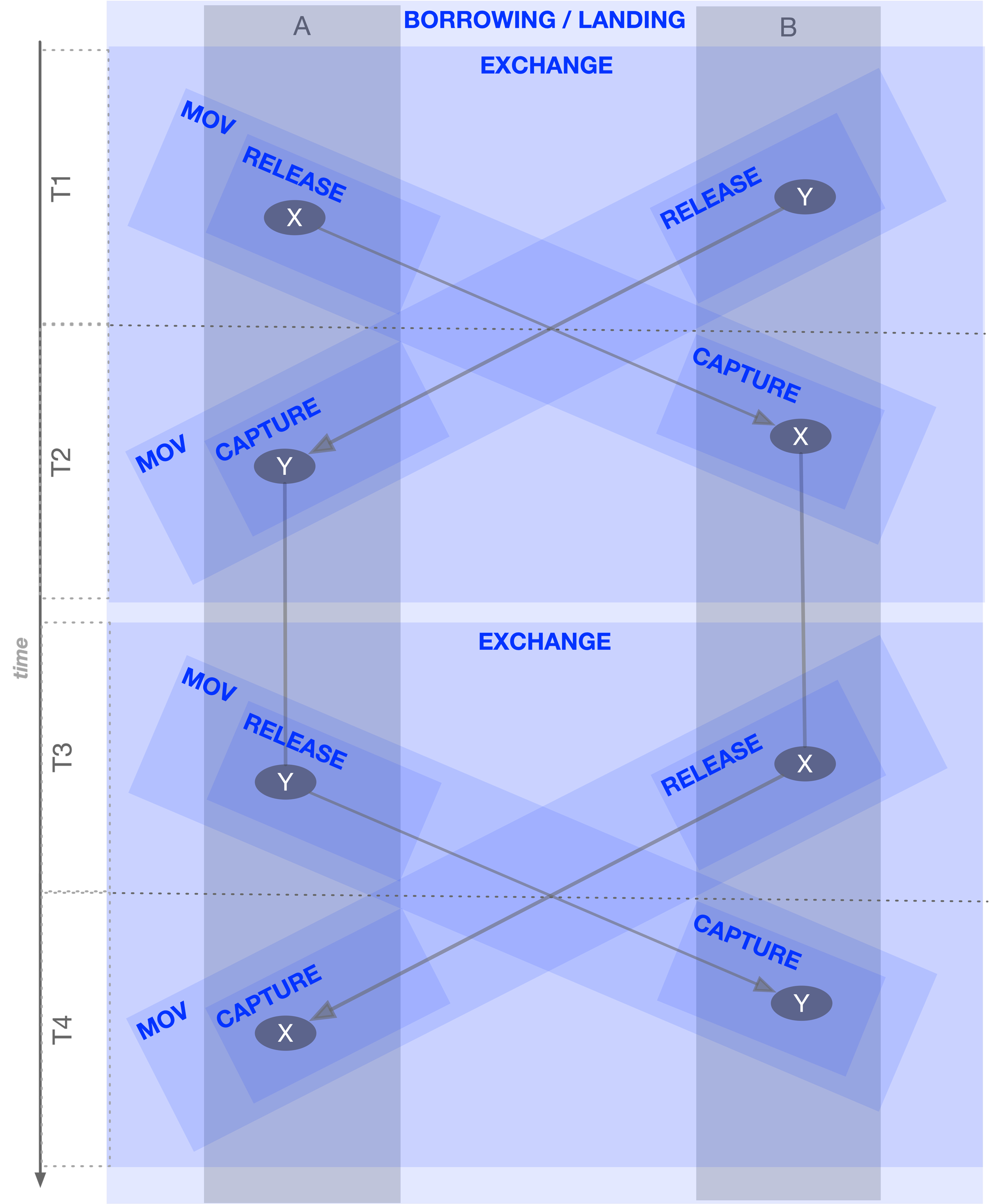

transaction, option, custodian, nostro account, position (both settled and pending), settlement instruction, pre-advice, borrowing-landing, corporate action, reconciliation, netting, and more.

The only domain-specific element is the label. The underlying structure—and therefore the semantics—is general. This is being demonstrated in the examples where a domain-specific “nicknames” are given to more general, abstract configurations.

While trade processing is the target domain discussed here, DCM is equally applicable to any domain where contracts between multiple parties are central.

By contrast, DCM is not applicable for purely technical domains such as image processing, data storage, or specialized niches like map navigation or threat detection in self-driving cars.

DCM is essentially a full-fledged formal theory of contracts as socio-cognitive constructs. Thus, the way DCM automates (digitalizes) contract execution mirrors the way human beings do so with their brains (on subconscious, unreflective level).

DCM focuses on business domains rooted in natural human activities—and as cognitive science over the last 50 years has shown, this list is far broader than it may seem at first glance.

The main hypothesis of applying DCM is: once you remove all the general cognitive structure from the contractmanagement domain, no structure remains unaccounted for. There is nothing left to ‘code‘ after formalising the domain within DCM.

None of the elements of DCM were specifically built for, or intended to exclusively serve, the financial domain.

The only domain-specific elements are the labels attached to the structures that DCM operates on. DCM is grounded in general concepts and theories from cognitive and brain sciences, which have no inherent knowledge of the trade processing domain.

Yet, elements that appear highly specific to trade processing are rendered directly within DCM—without requiring any additions or the introduction of domain-specific semantics. The core of DCM remains agnostic to the trade domain, yet is capable of expressing its concepts fully.

Concepts from trade processing that may seem unique or exclusive to that field map directly onto pre-existing building blocks within DCM. In other words, seemingly specific trade-related terms arise naturally within DCM, even though it was never designed specifically for them.

Why It Matters?

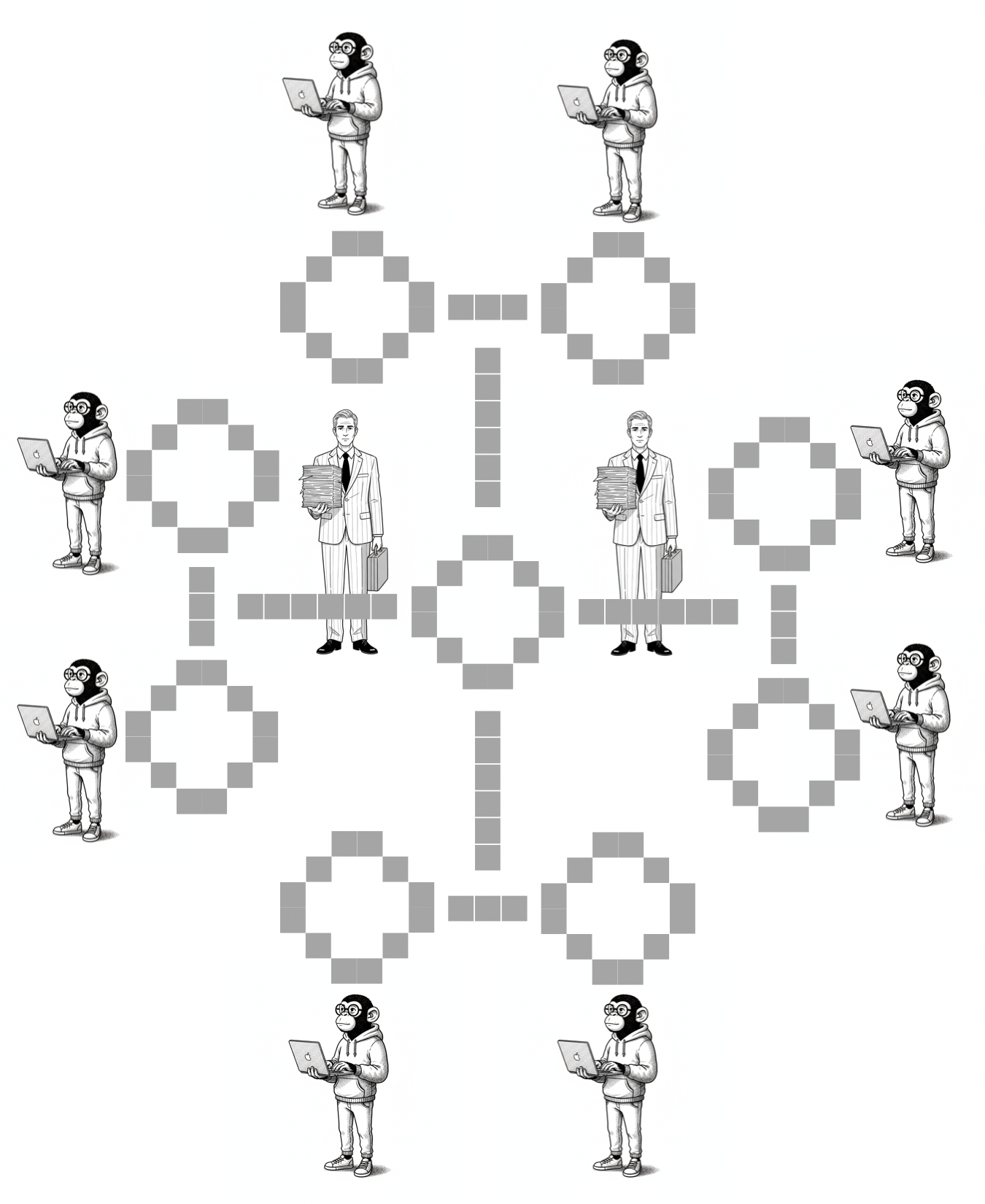

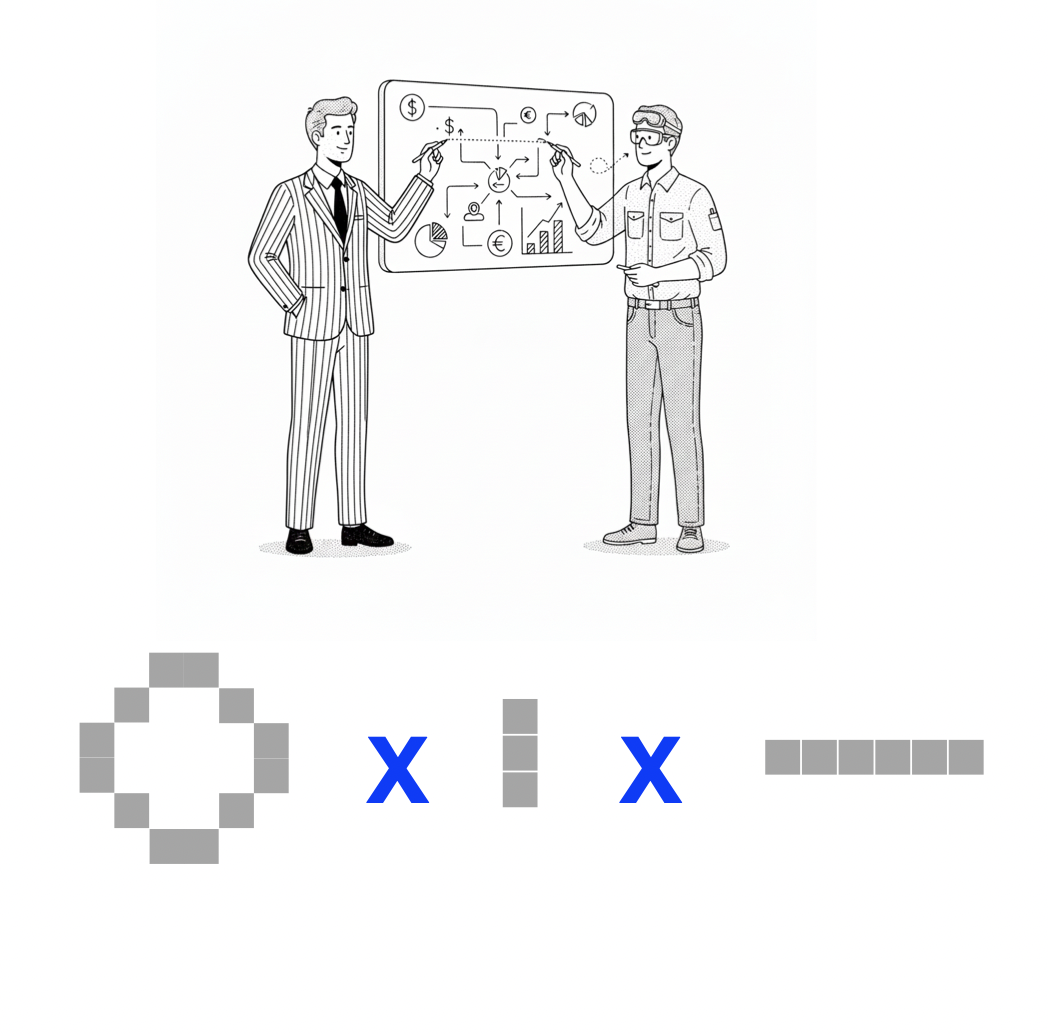

many FTEs for many months

few FTEs for a few days

DCM enables complex changes and extensions to be made to already sophisticated systems in a matter of days by a few people —changes that would typically take months or even years for large teams of developers to implement using conventional methods.

Equally important, it offers a level of reliability and security that is practically unachievable with traditional approaches.

This comes at a cost: it requires adopting a new foundation, a new basement. However, it integrates seamlessly with traditional systems, making it possible to blend legacy IT systems with the new architecture.

The benefits of this method easily overweight the costs for mid-to-large-scale systems that are expected to operate for years and are mission-critical, demanding high levels of stability and correctness. This method is not intended for small, trivial systems with minimal business logic or low operational importance, where traditional coding methods work just fine.

There’s no need to descend to the technical level (no coding), and no need to fill in every detail at the business level either (no repetitive or redundant requirements). Simply describe the contracts you want to have in their minimal form. Everything else will be inferred automatically by DCM in a deterministic manner, and you can always ask why something happens or how something is implemented and get a meaningful answer.

Key distinguishing features

Semantic Transparency

At the heart of DCM lies the principle of semantic transparency: what you see is what you get. The structures you see in DCM are the actual structures of the business domain itself—not just technical constructs or intermediaries. This ensures that, when building with DCM, the business domain remains directly visible and transparent, both in the code and in the running software.

In DCM, meaning resides in the structures themselves.

By contrast, in traditional programming languages meaning is imposed externally and only made visible through naming conventions when attaching labels to technical elements.

Traditional code has a shallow dispositional semantics: it operates through accidental correlations rather than intrinsic structure.

Human Scaling

Traditional software is designed around the constraints of computer hardware, not the capacities and limitations of the human mind. As a result, technical solutions often become so complex that people struggle to keep an efficient grasp—whether in understanding what the system is actually doing or in making changes to implement new business features.

DCM takes the opposite approach: it employs mechanisms modeled on how human cognition (reasoning) work, grounded in decades of research in cognitive linguistics and brain sciences.

This preserves a human scale even within large and sophisticated software systems—keeping them easy to change and extend, and avoiding the trap of software losing its malleability as code size increases.

Perspectivity

DCM lets you overlay multiple perspectives on the same content.

The system ensures that these different views are complementary and non-contradictory, enabling the multidimensional whole to be automatically reconstructed from multiple projections—without requiring you to confront the full complexity of that whole directly.

This preserves human-scale reasoning.

Thus, DCM employs the so-called collage mode of composition, which allows overlap between parts.

Traditional programming languages, by contrast, are built on a Lego-block model of composition, which implies exclusivity of representation.

As a result, there cannot be multiple complementary projections: there are no cross-cutting hierarchies, only a single exclusive hierarchy that must capture all the variety of the content.

Agency

action guidance as raison d’être

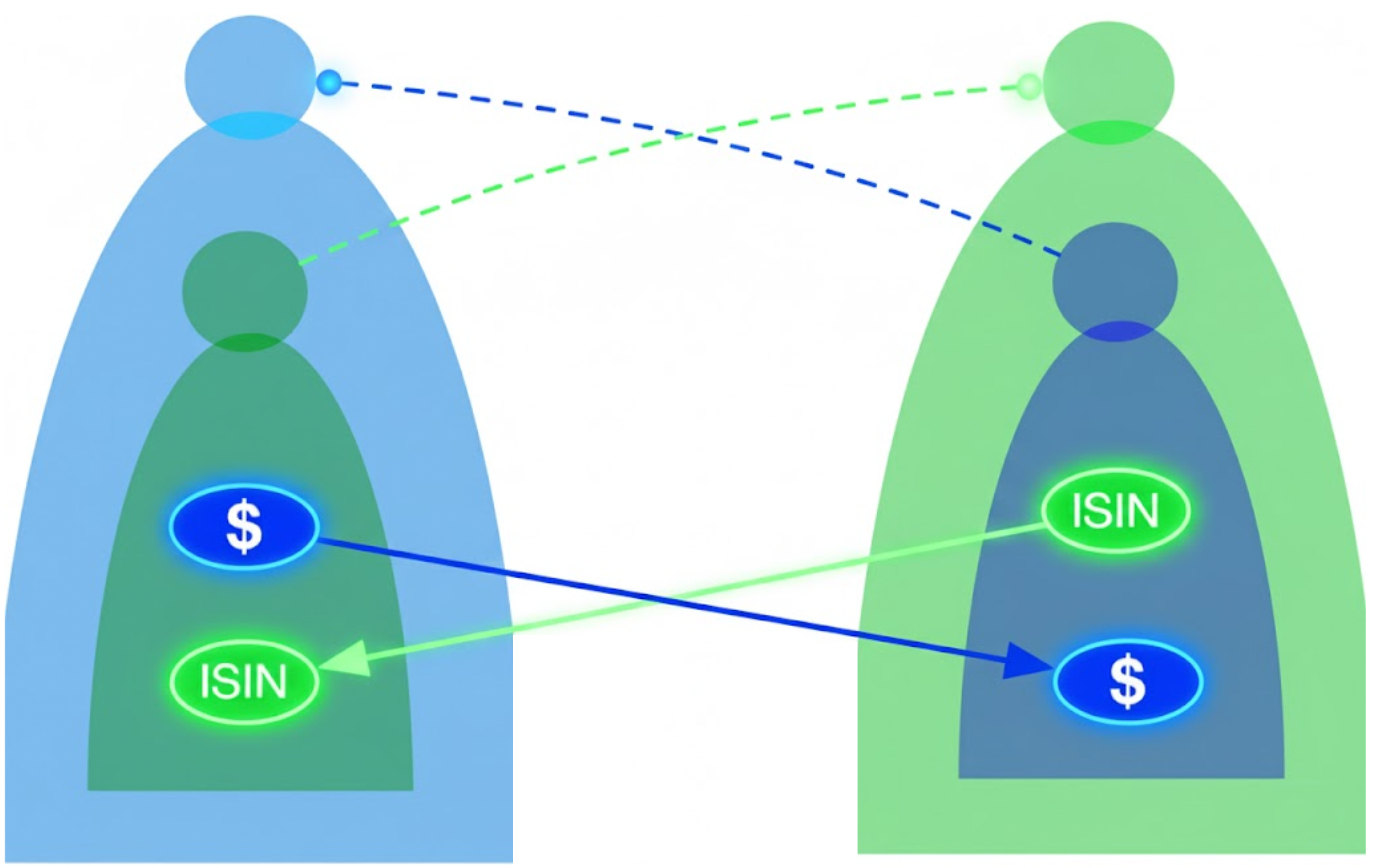

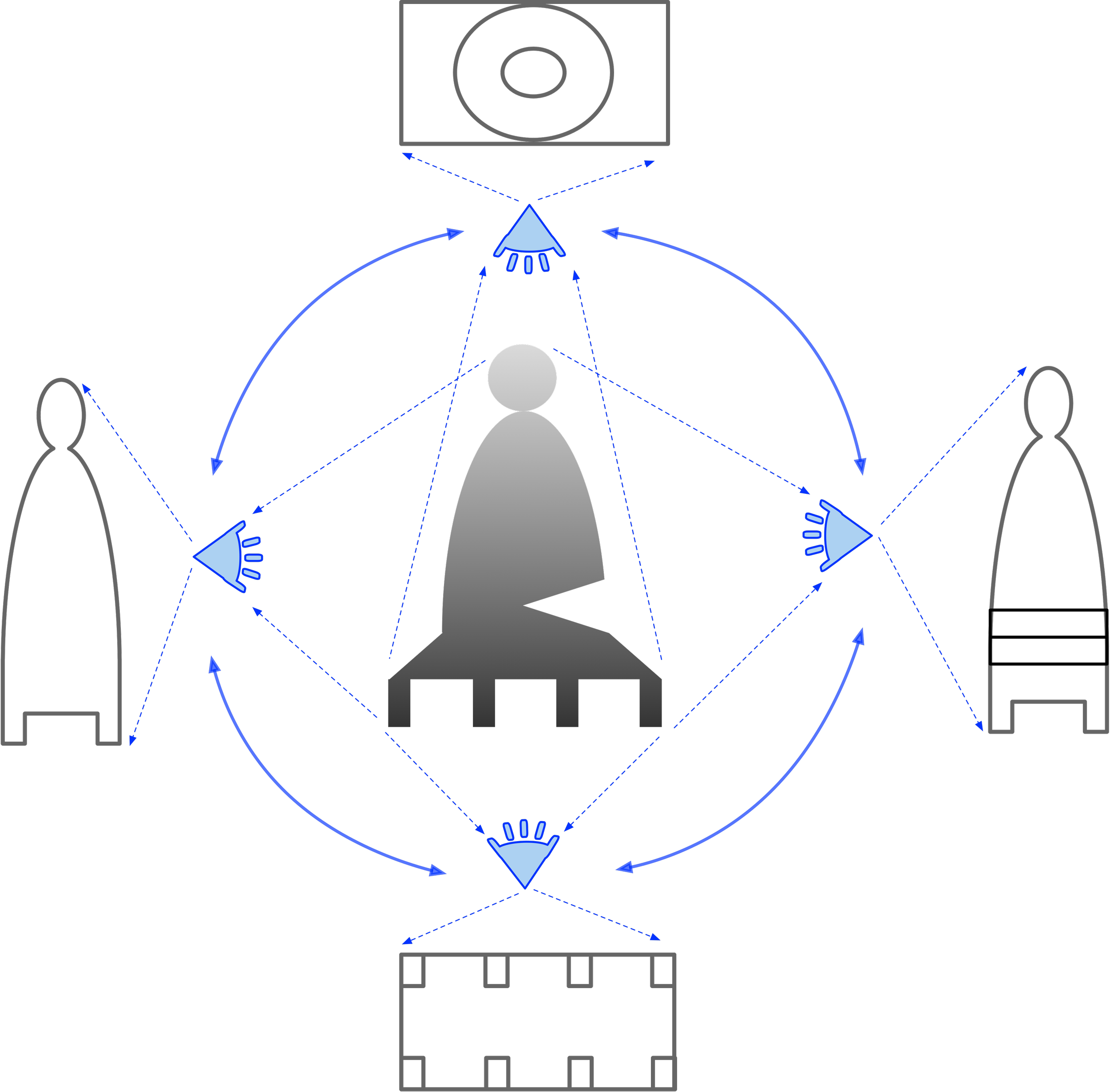

DCM is based on a model of intersubjectivity that combines two notions of space: the subjective space of agents (e.g., parties to a contract, each having their own perspective) and an objective space representing the shared world. This objective space acts like a map in which each agent can step outside their own ego-centered perspective and understand the points of view of other agents.

Contrary to DCM, the traditional approach does not even recognise agency as such; there is no notion of dynamics, interaction, or an explicit temporal dimension in the implementation domain. There are only arrangements of memory cells whose values are numbers or characters.

This simply reflects the fact that programming languages are not really languages, but dressed-up instructions for computers originally designed for number crunching.

Generating Kernel

Following the natural path to build systems

The way to build with DCM is first to understand how something comes into being—what processes cause the appearance of a particular structural element, not just what the element is on its own, detached from the process that generated it.

It is like building a tree: follows the same way to build a tree as nature does : grow it from the seed.

If a different tree is required, the DCM approach would involve changing the seed or intervening in the growth process at the right moment—for example, by placing a barrier to limit the tree’s width or height.

Contrary to DCM, the traditional approach is to build an already gown up tree, simply by adding elements together.

This method does not reflect the tree’s morphology; the relationships between branches and leaves are lost. All elements are treated as equal, being given in their current shape and “appearing all at once” or as “pre-existing.”

This is inefficient as this method can not rely on the automatic replication of structure along the growth path (of change of the seed changes all the leaves in a tree) that the DCM approach is based on.

Modelling Relation

The formal relation between business and software

The way that DCM looks at the task of building a software system that runs a business is similar to how a biologist builds a model for a living organism.

It starts by acknowledging that solving this task involves two different domains, not just the task itself: the software domain and the business domain.

DCM then follows a formal framework that aims at establishing a specific relation between these two—the modelling relation—which ensures that the software is a model of the business and not just a superficial imitation.

Contrary to DCM, the traditional approach does not acknowledge the existence of the business domain as such; hence, the business domain manifests itself only informally as vague software requirements, lacking formal structure.

Another problem is that the business domain is treated as an afterthought, in the sense that it does not serve as a fundamental factor shaping the technical domain.

Rather, the business domain appears as a post-factum application of the technical domain (hence the term “business application”), where the latter was created prior to and without an understanding of the former.

How it works

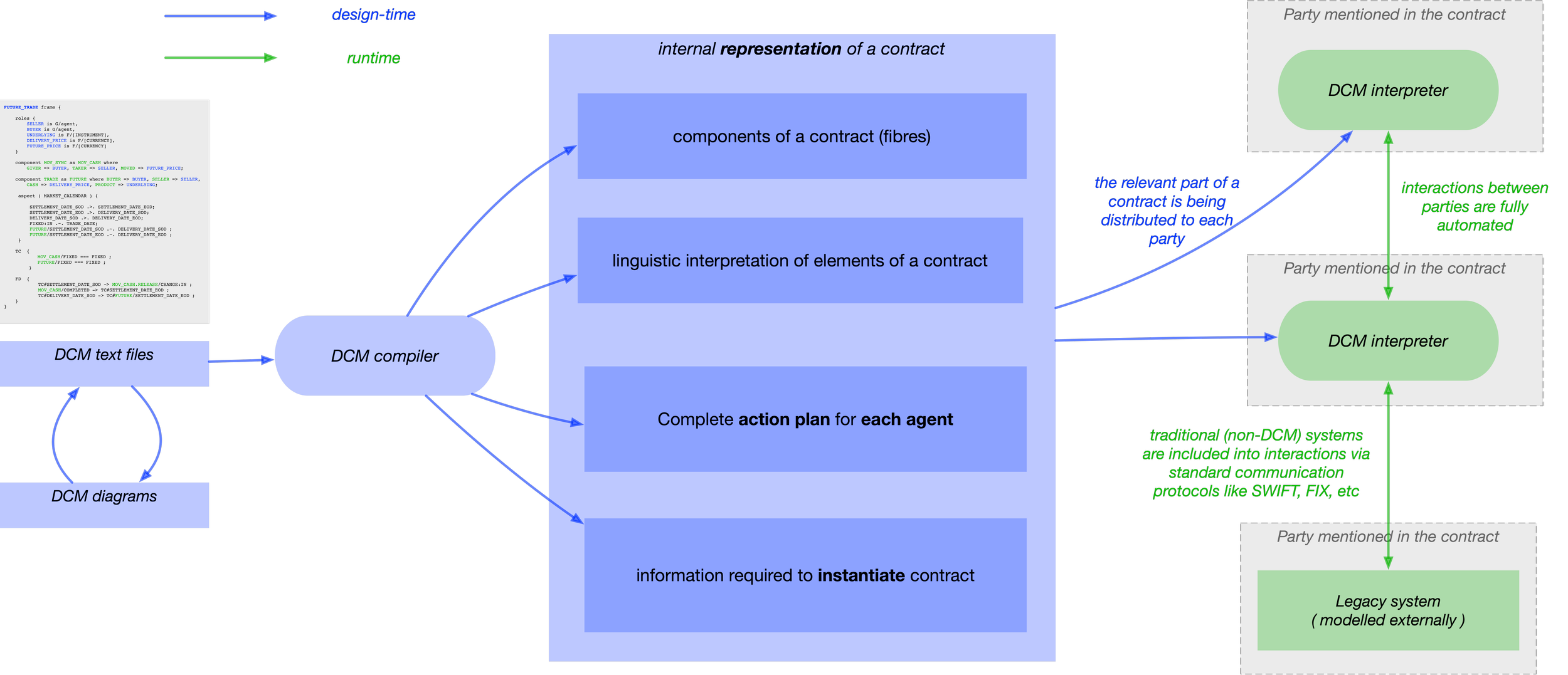

To implement a software system that executes a contract using DCM, the following steps are followed:

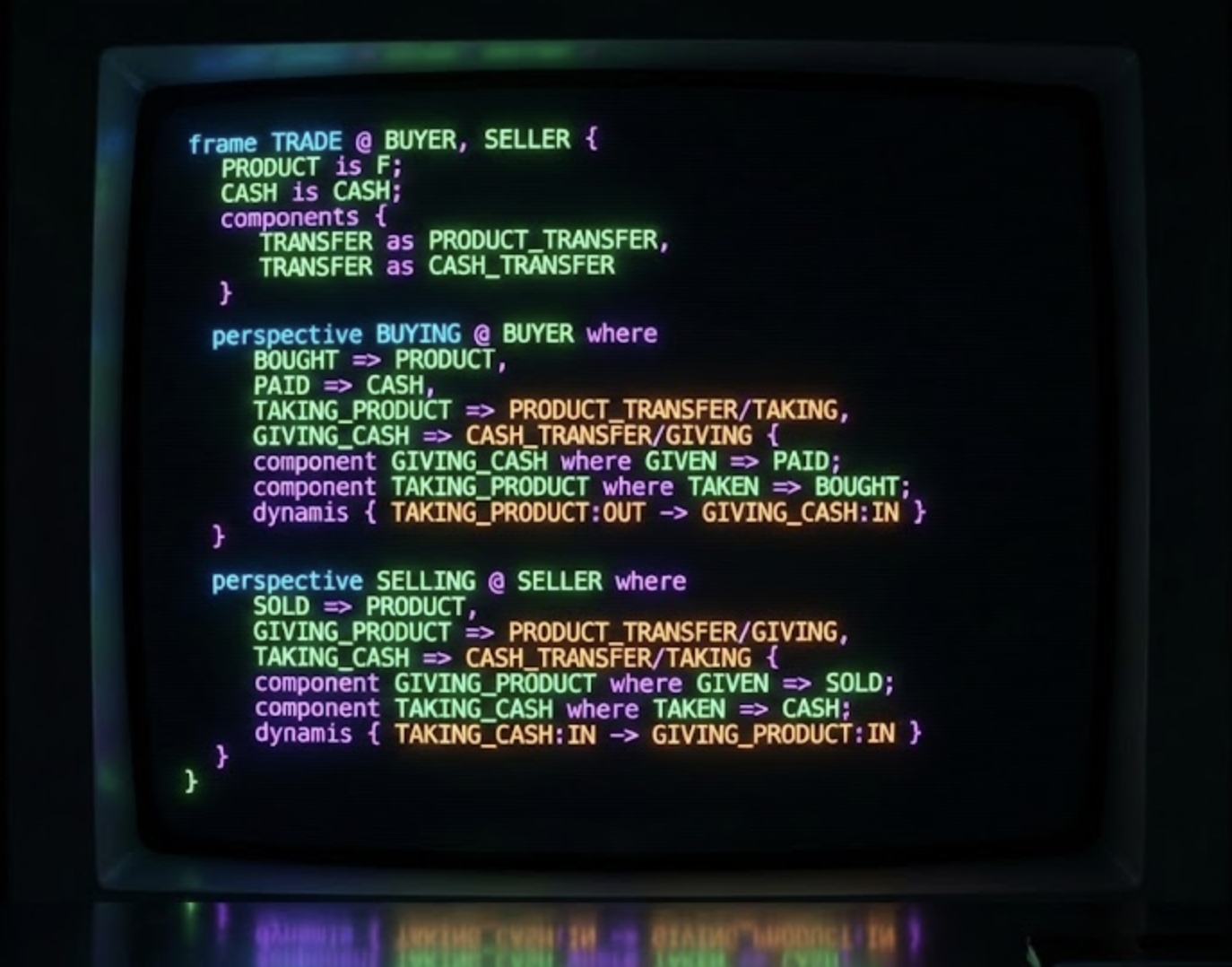

1. Write a formal description of the contract—either as text files in the DCM format or as diagrams. These artifacts represent the “source code” of the contract.

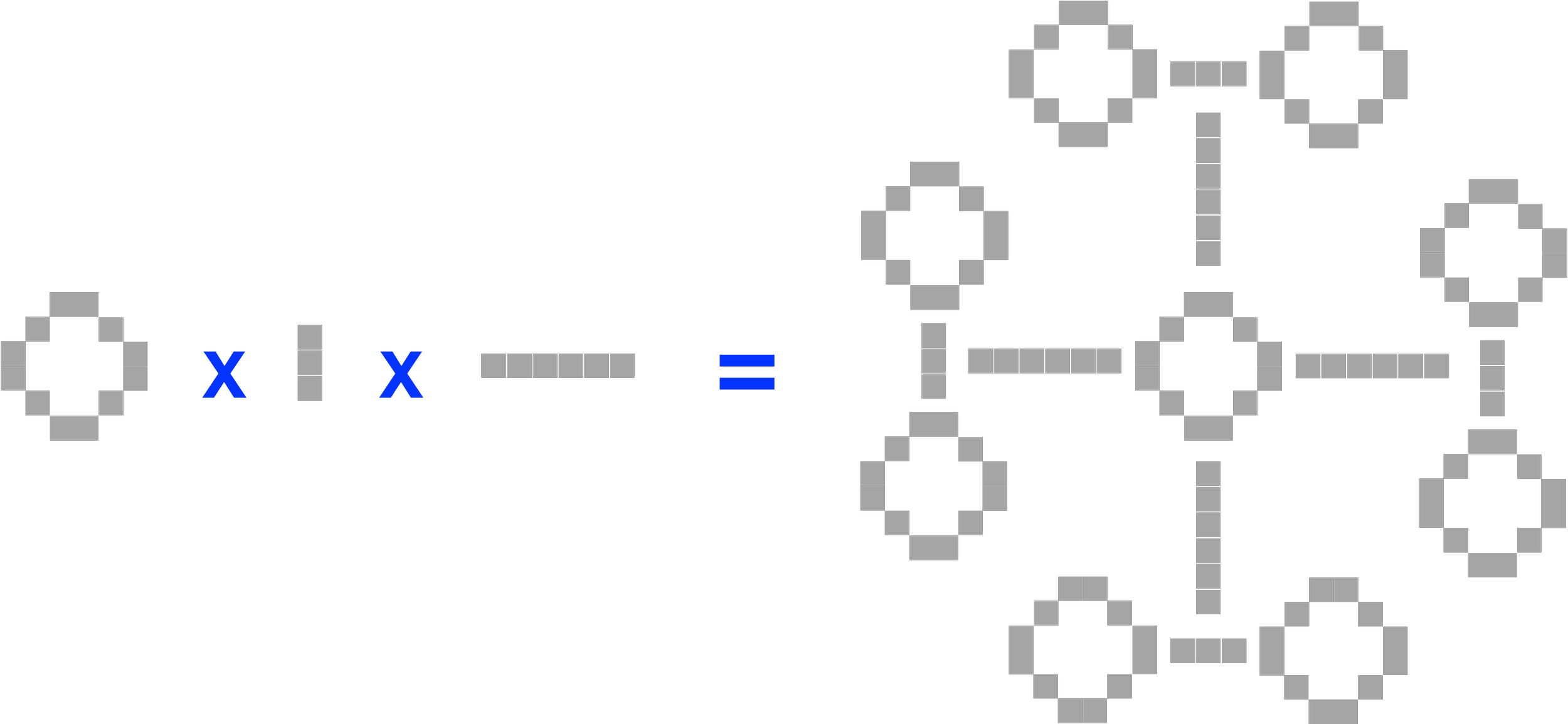

The core mechanism for building structures in DCM is the notion of a frame and layering frames over one another, like elements in a collage. For example, to build a system that executes a TRADE settlement, a TRADE frame is constructed from more primitive frames and then contextualized with other frames, such as CUSTODY. The resulting construction is called a construal (a term borrowed from cognitive linguistics).

2. Feed these artifacts into the DCM compiler, which performs extensive inference and generates an internal representation of the contract. This includes all information required to instantiate a new contract, as well as a complete action plan for each party involved—defining what each party must do to fulfill its role. This step succeeds only if the contract description is consistent and executable. If the description is incomplete or contains conflicting actions, it will fail to compile. In essence, this step allows DCM to “fill in the gaps” in the description, much like how the meaning of a sentence is constructed from just a few grammatical and lexical cues.

3. Each party receives the relevant portion of the contract, including a script for playing its role. In real-world scenarios, any contract typically depends on the existence of other contracts, each involving only a subset of participants from the main contract. For example, in a TRADE contract, the BUYER may have a CUSTODY contract set up with its CUSTODIAN, which the SELLER does not need to know about, since it is not a participant in that custody agreement. As a result, each party ends up with its own relevant set of contracts that define its role—what it must “perform on stage.”

4. Non-DCM systems can participate in contract execution via existing communication protocols such as SWIFT or FIX. A mapping must exist between these protocols and the DCM system. For instance, a DCM system communicating with a traditional system via SWIFT will interpret the content of SWIFT messages in DCM terms, and vice versa. In the TRADE example, certain actions in DCM correspond directly to settlement instructions and pre-advice SWIFT messages—so DCM actions of the info pane can be mapped one-to-one with such protocol messages.

Note that any real-world system will include many interlinked contracts, meaning that a given party’s action script is compiled as a superposition of multiple contracts.

Why D.C.M. ?

D stands for “Deep”, because CM models capture causal relationships within the content they represent. This enables rich inferential chains, allowing the system to generate content automatically that would otherwise need to be built (coded) manually.

C stands for “Cognitive” (or Conceptual), reflecting the fact that the approach is grounded in cognitive science and the scientific study of conceptualization—in other words, how thinking and understanding works.

M stands for “Models”, because these formal representations are intended to serve as models of the target domain, standing in a formal modeling relation to that domain.

Find out more

Investigate the difference between DCM, programming languages and AI/LLMs

Example of using DCM to formalise the notions of future and option

See how DCM can be applied to implement the settlement of a trade using just a few pages of conceptual description.

An introduction to a theory that DCM is built upon including frames, vantages, modelling relation and more

Follow the DCM story from the beginning, starting with the foundational question that arises when building large software systems that run a business.